Back-ender Charlie Phippin, one of the early birds at Nha Trang, tells what it was like to volunteer for an assignment nobody really knew much about and what it was like to start a detachment from scratch. Thanks Charlie!

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

Early in 1966 twelve airmen, led by SSgt Ed Bendinelli, were selected from a large group of volunteers at the 6917th Security Squadron at San Vito, Italy, to go to Viet Nam. This is my version of how we became part of the beginning of Det. 1 of the 6994th at Nha Trang—the airmen who later became humorously known as the "Dirty Dozen".

| SSgt Ed Bendinelli A1C Gary Baxter A1C Patrick McCafferty A2C Charles Phippin A2C Patrick Moree A2C Mitchell Cooper |

A1C Valenti Vera |

We were sent TDY to Wiesbaden, Germany for Class III Flight Physicals and Physiological Training starting 21 April.1 In off time, we toured the area by boat and train, taking in the local touristy places. After returning to Italy, we had to train and qualifying with the .38 caliber pistol on the beach firing range of the Italian military at Leece. DEROS for eight of us was set for 9 July and four set for 23 July 1966.

Getting to Fairchild AFB, Washington, for survival school during that period was made difficult by a nationwide airline strike. We were stranded in New York when we arrived stateside. Mitchell Cooper's mother came from New Jersey to take us to her home for a short period while transportation was secured. I did not go to Mrs. Cooper's: I took a bus home to Maryland and returned when called. We secured a flight on a military-only flight provided by Northwest Airlines and we started survival school on 11 July. After taking leave, we reported to Hamilton AFB, California, for M-16 training, after which we were flown to Viet Nam, landing in Saigon. At that point, Vera, Baxter, Curtis, Cooper, and Halunen were assigned to 6994th at Tan Son Nhut. The other seven were sent to Det. 1 at Nha Trang.

|

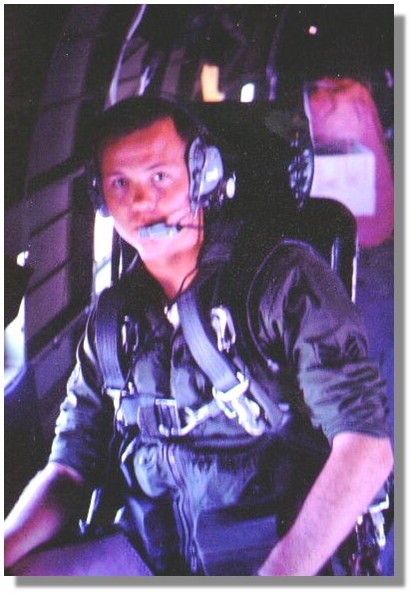

I don't think any of us, except maybe Bendinelli, knew what we were going to do when we volunteered in Italy or even after we arrived at Nha Trang. It was there that we were informed of the mission and how it was to be accomplished. No planes were there as yet, so we helped build housing/huts for the base as well as helping our unit prepare for the arrival of our planes. When the planes began to arrive, we began training on operating the equipment, job requirements, and protocol. As the aircraft arrived, certain ranks—career NCOs and A1C personnel—were trained first and certified as trainers for the remaining group. The training missions they flew were operational in nature but where, I do not know. There were problems with equipment, and missions aborted frequently. As far as the ARDF part, I was more aware simply because I was a school-certified FLR-9 operator and knew about plotting and DF capabilities. Just where our missions were flown was not much of importance to most of us—how many fixes made was the key. It needs to be noted that at the time the highest ranking operator was designated as the mission specialist and he carried the black bag with the code-books2 and other materials needed for the mission. Once in flight, the code-books were given to the "Y" operator. The junior operator usually started out sitting at the "Y" position, which was just the radio, no console.3 He was responsible for copying the target callsign, etc., with pad and pencil then encoding the fix info and transmitting it to the ground contact. If leaflets were dropped, this was a secondary job. Of course, the operators would switch positions as both were capable of working the "X" and "Y" positions. |

|

|

Towards the end of the first year, equal rank operators flew together but one was still designated to be the mission specialist. At the end of the mission, the mission specialist transported the fix sheets from the navigator and code-books and materials to the operations compound. The junior man was done for the day, but sometimes we just tagged along to ops. For this reason, most of us did not know much about where our fixes were found. We became aware of our territory by knowing certain locations such as air strips and harbors.

We operated in the provinces north and northwest of Nha Trang, including Pleiku, which had no planes then, and Kontum. We flew a lot along the coastal areas because of the enemy moving supplies and munitions on the water areas. MARKET TIME4 fixes were made with some frequency. Places I remember by name in which we frequently operated that year were: Ninh Hoa, Ban Me Thuot, Qui Nhon, Pleiku, Kontum, Dak To, Tuy Hoa, An Khe, and Phu Cat. We did fly extended two or three day missions, laying over in Pleiku and Da Nang, but exactly what specific areas, I was not familiar with. The highlands around Pleiku were always hot with fixes just about anytime I flew there.

Days not flying consisted of squadron duties such as manning the squadron radio, morning crew pickup, and crew shuttle work. I flew many missions with TSgt Floyd Morse but over my time, I flew with just about everyone assigned. I never gave a thought about the danger until the loss of Tide 86 and its crew, my co-workers and friends. The memorial service was a solemn occasion as their loss was felt by everyone, but the work continued with more ardor and dedication, in their memory.

In the summer of 1967, I was one of the group led by A1C Don Wade that prepared the banquet for the one-year anniversary of the unit, held on the rooftop of MACV Headquarters to celebrate a successful first year. [Click here to view the banquet menu.] The infrequency of personality conflicts attest to the respect each had for the other and the mission we shared. The entire unit was, without a doubt, the most dedicated and professional I have been associated with, ever. I was and am honored and proud to have been a part of that group and the groups that followed.

_____

Editorial notes:

1. This speaks to the general lack if knowledge and air of secrecy surrounding PHYLLIS ANN. There was no need to train Gooney Bird crews on the use of oxygen masks, much less ejection seats! Obviously the nature of the mission was largely unknown at this time.

2. These code books were "one-time" pads used to encrypt target data for transmission to the DSU.

3. More evidence of the hurry up nature of project PHYLLIS ANN. The earliest aircraft to arrive in country were definitely "bare bones." Ed Bendinelli reports that the first back end crews were not even issued flight suits.

4. MARKET TIME was the USN's program of interdicting vessels on the high seas suspected of carrying enemy supplies to South Vietnam.