The Outlook in January

General Westmoreland’s strategy as outlined in the joint U.S./RVN Combined Campaign Plan for 1967 focused the American effort “on the enemy base areas and supply systems, the Achilles heel of the VC/NVA.” Ground operations launched in late 1966 had in fact hurt the enemy and in early 1967 he appeared to be trying to avoid large-scale confrontations. The battle for “hearts and minds” would of course continue, now under the glorified title of Civil Operations and Revolutionary Development Support (CORDS) and headed by a civilian Deputy Commander, MACV. The South Vietnamese would, when COMUSMACV saw fit, take part in combined offensive operations but ARVN’s primary duty would be to provide security in government-controlled areas. Top priority for MACV’s offensive operations would be the communists’ War Zone C along the Cambodian border northwest of Saigon, home to COSVN and its associated combat elements—the most obvious direct threat to the South Vietnamse capital. Second priority was given to enemy base areas in southern I CTZ, followed by similar targets in coastal Binh Dinh province.

The COMPASS DART mission remained unchanged from that of PHYLLIS ANN: “To conduct daily, day/night, all weather ARDF operations against enemy operated transmitters in the RVN and permissive areas ot Laos as a basis for tactical exploitation in support of requirement established by COMUSMACV and Commander of 7AF.” The EC-47 fleet was approaching programmed strength; flying hours and sorties went up accordingly. For January-March, the three EC-47 outfits logged 1,998 missions, an average of 22 per day. These numbers would steadily increase as the last few aircraft trickled in and maintenance and supply issues were resolved.

The I Corps Wars

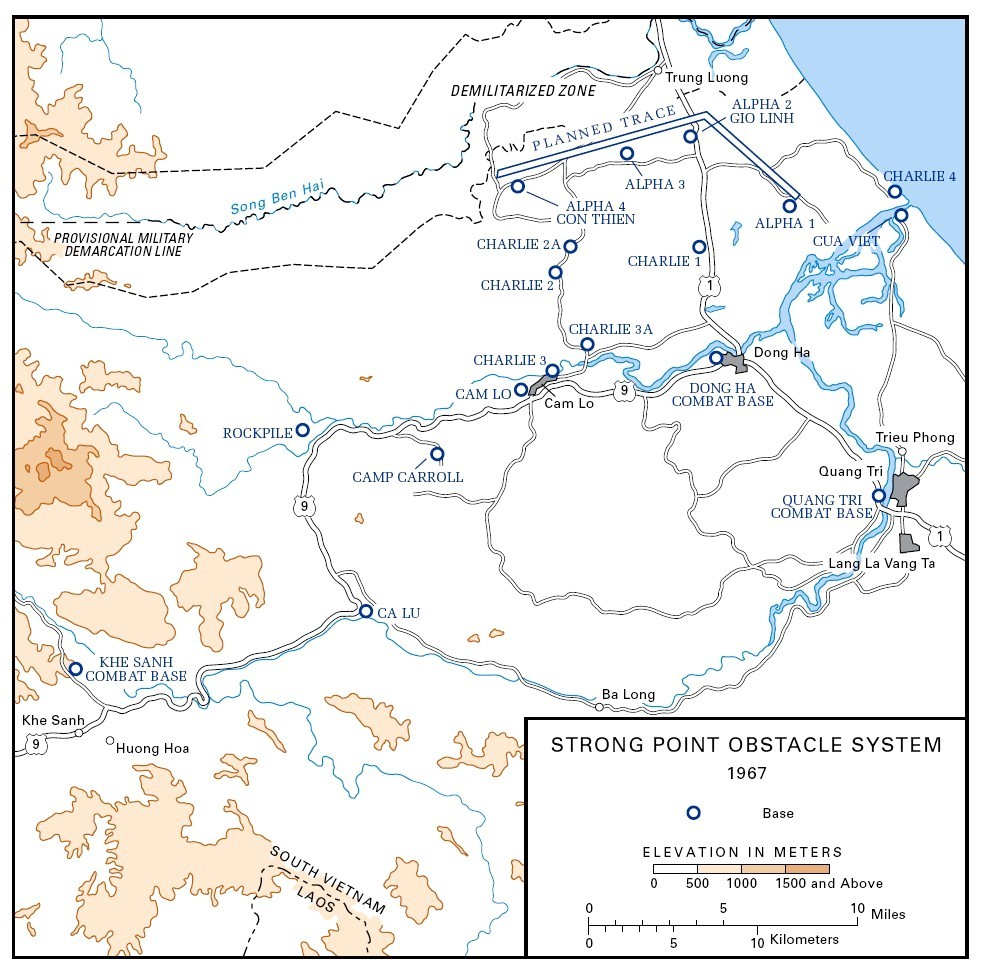

In I CTZ, III MAF essentially fought two separate wars. Along the DMZ, the 3d Marine Division (MARDIV) faced its long-time enemy the NVA 324B Division, with three other main force NVA divisions believed to be in the area. The Marines' positions stretched from the 3d MARDIV forward command post at Dong Ha westward to Con Thien, Cam Lo, Camp Carroll, and The Rockpile. At the end of the line stood Khe Sanh and the nearby Special Forces camp at Lang Vei, a few miles from the Laotian border.

|

PHYLLIS ANN had provided much Close Tactical Support to operations HASTINGS and PRAIRIE in late 1966; both COMPASS DART and DRILL PRESS would continue that support throughout the first half of 1967. In mid-February, the Pleiku ARDF mission was dramatically expanded. The Marines continued to keep a close eye on their old adversary, the NVA 324B Division, now believed to be located north of the DMZ, just out of ARDF range. In an attempt to remedy the situation a new ARDF area was drawn up off the coast of North Vietnam, extending from the DMZ north to Dong Hoi. The new missions were flown "feet wet" (i.e., over water) but results were apparently inconclusive. For the Marines, the Demilitarized Zone was anything but. The U.S. rules of engagement permitted the North Vietnamese to treat the DMZ as sanctuary not much different from those they enjoyed in Laos and Cambodia. The NVA could shell as they pleased, launch ground attacks when circumstances were right or retreat to safety if things went wrong—all without the necessity of holding back defensive forces to guard their own positions. The Marines, forbidden to enter the DMZ or to fire on the enemy positions, could do little more than dig deeper and prepare for a ground assault if it came. |

|

That would change in late February as American artillery was at last allowed to fire into and north of the DMZ against strictly military targets. Their haven suddenly no longer safe, the North Vietnamese quickly replied in kind. The long-range punching match would continue for months. Meanwhile both sides, mostly unbeknownst to the other, prepared to renew ground operations.

On 27 February, as Operation PRAIRIE II got underway, a Marine recon team out of Cam Lo stumbled onto elements of what proved to be a regiment of the NVA 324B Division. American firepower took its usual toll on the NVA, who withdrew only after inflicting heavy casualties on the outnumbered Marines. On 8 May, the 13th anniversary of the fall of Dien Bien Phu, the NVA launched a heavy ground attack on Con Thien. (See map.) Situated on a hilltop less than two miles from the DMZ, this outpost offered “the best observation in the area” making it an object of importance to both the Marines and the NVA. The fighting, much of it hand-to-hand, was intense. In the five-hour battle the Marines suffered 44 killed and 110 wounded. The NVA left 197 bodies behind, along with many weapons, including flamethrowers. Two days later, the Marines saw three surface-to-air missiles blast skyward from the DMZ. One of them downed an A-4 Skyhawk; the first confirmed use of SAMs in South Vietnam.

At the western end of the line Khe Sanh, dominating as it did the surrounding terrain, served as a strategic American observation post/fire base and, in the minds of both the NVA and COMUSMACV, a potential launching pad for any attempt to physically cut the Trail. While the Marines were occupied with PRAIRIE and other operations to the east, elements of a newly engaged NVA Division, the 325C, surrounded the base with well fortified positions then attempted to overrun it, Dien Bien Phu-style. The Marines, aided by more than 1,100 close air support sorties and 23 B-52 strikes, fought their way clear and occupied the surrounding hills as the NVA slipped back over the DMZ or into Laos. The enemy lost over 900 killed in eighteen days of attacks, but it cost the Marines 155 men to stop them. Operation HICKORY, a short-duration sweep lasting only 11 days, traded 119 Marine lives and more than 800 wounded for 367 claimed enemy dead. Much the same pattern would repeat through the ebb and flow of the PRAIRIE operations, which continued through the end of May. For the nearly year-long duration of the PRAIRIE series the Marines claimed a body count of nearly 3,000 enemy against 537 of their own killed in action, with another 3,400 wounded—an exchange rate the American public was already calling into question.

Action in Southern I CTZ

The presence of three or four NVA divisions near the DMZ and the possibility that the enemy might launch a large-scale invasion with the aim of establishing a “liberated zone” within South Vietnam naturally occupied most of the U.S. command’s attention during the first months of 1967. The Marines were spread thin. To free up more battalions to counter the emerging threat along the DMZ, COMUSMACV ordered the creation of a division-size army formation to reinforce southern I CTZ in the Chu Lai area. Designated Task Force OREGON, it was composed of units drawn from divisions elsewhere in country. T.F. OREGON would eventually be raised to divisional status as the 23d Infantry Division (Americal), a reincarnation of the WWII "Americal" division that relieved the 1st Marine Division on Guadalcanal.

|

Meanwhile, the 1st MARDIV continued its pacification and counterguerrilla operations. In the Da Nang area alone, the Leathernecks carried out no less than 36,553 company-size patrols, sweeps, and ambushes during January-March. These small unit actions “established a tedious balance in the ‘cat-and-mouse’ game of subduing local guerrillas” but when “confirmed intelligence reports” indicated the presence of main force enemy units, large scale operations such as DESOTO and UNION were set in motion. “Confirmed intelligence reports” no doubt included many ARDF fixes, although security considerations precluded precise mention of intelligence sources in contemporary after action reports or in official histories written years later. Close Tactical Support in I Corps The 6994th and TEWS histories for the period are largely silent as to COMPASS DART mission results in I CTZ, mentioning only that CTS was provided for certain operations—notably the long running PRAIRIE series—but without further details. The Pleiku-based EC-47 teams flew the majority of their missions in the TIGERHOUND (Laos) and DMZ areas. Most were for “continuity and development” (C & D) of enemy communication networks, although some were tasked as CTS missions; as of 30 June 450 sorties had been flown in support of 25 allied ground operations. Fix numbers rose from 465 in January to 2,000 for June. In the first six months of 1967, the Electric Goons out of Pleiku nailed 7,652 enemy targets. |

|

The 361st TEWS/Det. 1, 6994th team at Nha Trang noted that sorties had been flown in support of operations DESOTO and RIO GRANDE, although few specifics were recorded. The latter of these operations was “of historical note” in that it featured a tri-nation command post coordinating several ARVN battalions and two ROK Marine battalions along with the 5th U.S. Marine Corps regiment. The ARVN drew rare praise for bashing enemy units attempting to flee contact with the Koreans.

DRILL PRESS remained heavily involved in support of III MAF, having operated out of Phu Bai since the previous September in close cooperation with ASA’s 8th Radio Research Field Station. Working mostly against NVA 324B networks passing low level encrypted traffic, DRILL PRESS collected more than 1,300 hours of Morse transmissions containing some 3,150 messages, about two-thirds of which were readable. The results, ultimately translated into 2,160 intelligence reports, were quickly and consistently "proving to be invaluable.”

Looking Ahead in June

From start to finish of the Vietnam War, the U.S. faced one seemingly insoluble problem: How to stop, or at least seriously impede, the flow of men and material from North Vietnam to the battlefields in the south. By mid-1967 it was apparent that the tightly controlled ROLLING THUNDER bombing campaign had not convinced the North Vietnamese to begin peace negotiations, nor had it seriously diminished infiltration into South Vietnam. Political concerns, some of them valid, others less so, ruled out any large-scale conventional land attack against the Ho Chi Minh Trail or even the pursuit of the enemy into his Laotian and Cambodian sanctuaries. Lacking authorization, and perhaps even the capability, to destroy the infiltration routes or to engage the enemy in his border sanctuaries, COMUSMACV was left with no alternative but to fight the communists within the confines of South Vietnam. If enemy infiltration could be drastically reduced, the ground war might be won with the forces already on hand. Otherwise, victory would require even more time and more U.S. troops—and a concomitant rise in the already unacceptably high casualty rate.

The idea that some kind of physical impediment might be thrown in the path of the intruders was not new, but in August, 1966, a civilian think tank under contract to DoD finally concluded “that it may be possible to design an air-supported barrier system to inhibit enemy operations on these infiltration routes.” Both CINCPAC and COMUSMACV expressed reservations as to feasibility and cost, but the SECDEF was willing to take a further look. McNamara liked what he saw and in September, 1966, he created a top-level task force to develop the scheme into a workable system. By early 1967, the project, initially named PRACTICE NINE, had been assigned “highest national priority.”

The barrier was to consist of four subsystems, two of which would encompass territory within South Vietnam south of the DMZ and the already designated TIGER HOUND and STEEL TIGER interdiction areas in Laos. These areas, one aimed at foot traffic, the other vehicular, would feature air-dropped munitions and sensors. Signals from the sensors (acoustic and seismic) would be picked up by orbiting aircraft which would then direct air strikes against the revealed targets. A third subsystem, “a ground barrier designated Strong Point Obstacle System (SPOS),” consisting of interlocking strong points (Alpha 1–4 on the map) along a cleared “trace”, backed by larger support bases to the south (“Charlie” on the map.) A final subsystem, not well defined, would deal with the no man’s land between the SPOS and the Laotian zones.

There was considerable opposition to the whole barrier idea, notably from the Marines, who would be responsible for manning the SPOS with troops drawn from their already stretched-thin ranks. The III MAF commander went so far as to suggest that such a barrier “was not going to be worth the time and the effort that would be put into it.” But orders were orders. By the summer of 1967, “the McNamara Line” was under construction.

Article by Joe Martin

Revised and updated, 06 October 2017